-

The campus and the velocity of sound

Jan 15, 2021

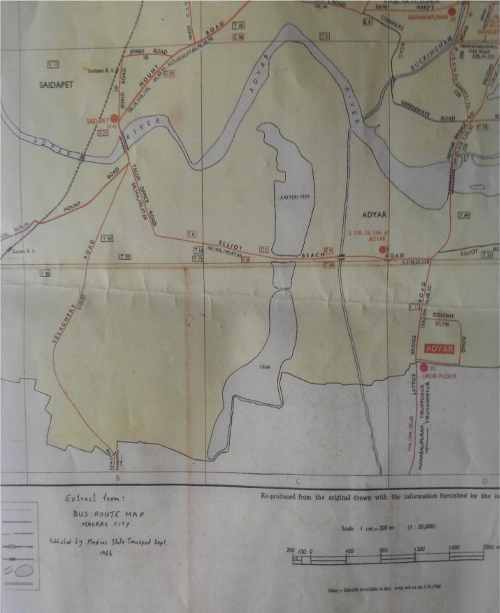

Kumaran Sathasivam

Download PDFThe picture alongside shows a part of a Madras City bus route map published in 1966. Areas such as Adyar and Saidapet are marked, whereas IIT Madras (more than 6 years old then), CLRI, the College of Engineering Guindy/Anna University and Raj Bhavan are not. Two water bodies, the larger one marked ‘Tank’, are shown occupying much of the IIT campus. These had presumably been connected with a third water body, lying to the north, marked as ‘Katteri Eri’, and had subsequently been separated by the Sardar Patel Road (then known as Elliot Beach Road). A comparison with a contemporary map will show the extent to which the road network in the area has grown in the last 50 years or so. The map was published by the Madras State Transport Department and is in the collection of Mr. Thomas Tharu (‘Tee Square’), alumnus of the 1969 batch of IIT Madras, who kindly allowed this photograph to be taken for the Heritage Centre.

Madras City bus route map published in 1966

Among the articles published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in 1823 was one titled ‘Experiments for Ascertaining the Velocity of Sound, at Madras in the East Indies’. The author was a person named John Goldingham.

Goldingham conducted his study over many months, beginning in July 1820. He used the sound of guns that were fired daily at two places: “At Fort St. George (Madras) a morning and an evening gun are fired from the ramparts, as is customary in fortified places, the former at day light, and the latter at eight o’clock in the evening”, wrote Goldingham. “At St. Thomas’s Mount, the artillery cantonment, morning and evening guns are also fired, one at day light and the other at sun set.” Goldingham made a series of observations from the Madras Observatory, at Nungambakkam: “All the experiments were made with chronometers, which had 100 beats in 40 seconds, sometimes by three observers, myself and two of the Observatory Bramin assistants, but generally by two: the observers having repaired to the station at the top of the Observatory building, a little before the expected time, and each holding his chronometer so that he could distinctly hear the beats, began to count the instant he saw the flash, and continued counting till he heard the report; the number of beats between the flash and report was then immediately put down upon a slip of paper, by each observer, without communication with the others, and the papers delivered to me for their contents to be registered...”

Goldingham measured the distances with great care: “first, by a survey made for the purpose, a base having been measured, and the angles taken with a great circular instrument ... Secondly, by using two or three of Colonel Lambton’s distances and bearings found by the trigonometrical survey.”

Goldingham’s account tells us much about the level of advancement of science at the time that it was written. So too does it offer hints that transport us back in time to Madras as it was 200 years back—a practice of firing guns twice a day at the Fort and at St. Thomas Mount, the existence of an active observatory in the city, the construction of a new building at that observatory.

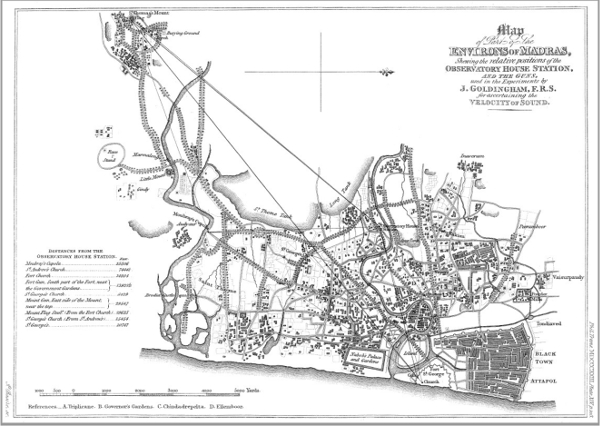

Goldingham’s publication carried a map that showed the relative positions and distances of the points. According to Goldingham, this map was “filled up from the best surveys, under the superintendance of E. Lake, Esq. of the Madras Engineers”, who he mentions is his son-in-law. I found the map engrossing. I thank Shyamal L. for drawing my attention to this map and thus to the article in which it appeared.

The following are the results deduced from the experiments in the different tables. I shall first give the general results from table I. and VI.

Results presented by Goldingham in his paper. The units he uses are inches, feet and degrees Fahrenheit. He uses commas in the numerical values as we would full stops

There are several points about the map that one finds striking simultaneously. The city is of course much smaller and sparsely built over compared with the present. The road network appears ludicrously rudimentary. One cannot even find a road along the Marina. That having been said, many of the roads that are shown seem to have been lined entirely with trees, including Mount Road and Poonamallee High Road. Naturally, there are no railway lines or the Buckingham Canal—these would come up later.

Places such as Besant Nagar and T. Nagar are not marked on the map—these places were non-existent when the map was made. Indeed, at the present situation of T. Nagar is a large water body, one bearing the name ‘St. Thome Tank’, and close to it is the ‘Long Tank’. On the other hand, the map does have ‘Race Stand’, ‘Moubray’s Cupola’ and ‘Brodia Castle’ marked on it.

And the spellings of place-names! We have Peeramboor, Inaveram, Porshewaukam, Chindadrepeta, Ellemboor and Tondiaved, which we can relate to current names. But what was the ‘Powder Mills’? An explosives factory? And what was ‘Attapol’, pray?

Of special interest to us of course are ‘Audyaur’ and ‘Gindy’, to the vicinity of which our eyes are drawn as we search for the place that would become the IIT Madras campus.

In November 1821 (a month in which Goldingham was still making his measurements, six months before he wrote up his article in the Philosophical Transactions), the government bought three contiguous properties at Guindy (the ‘Guindy Forest’), as a result of which it had some 1000 acres for development into the residential estate of the Governors of Madras. According to S. Muthiah’s book on the Raj Bhavans of Tamil Nadu, at this point there were three single-storeyed buildings at the place where the present Raj Bhavan stands. Presumably these are the buildings shown as a set of small constructions at ‘Gindy’ on the map.

There is no Highways Research Station marked on the map—it would have been very surprising if it had been marked because the HRS was established in 1954! There is a sharp bend in the course of the Adyar River in this region, and just outside this bend is an unnamed plot, marked in dotted lines on the map.

The College of Engineering (Anna University) is also not marked on the map. This is only to be expected. Although the precursor of this institution, the School of Survey, was established in 1794, the College of Engineering would move to the present location of Anna University only in 1920.It would seem that Audyaur was an unremarkable hamlet, for it is not connected to the rest of the city by any road. There was none worth marking on the map anyway.

And finally, the future IIT campus:: no feature is marked on it except for a water body that occupies a good part of it and space outside, one that bears no name.

Your response to Letter from Heritage Centre is welcome. Please send mail to heritage@iitm.ac.in

The Heritage Centre is located in the ground floor of the Administration Building, IIT Madras. It is open on weekdays from 9.30 am to 5.30 pm.

- Contribute

to the Centre -

Monetary

Support - Digital

Material